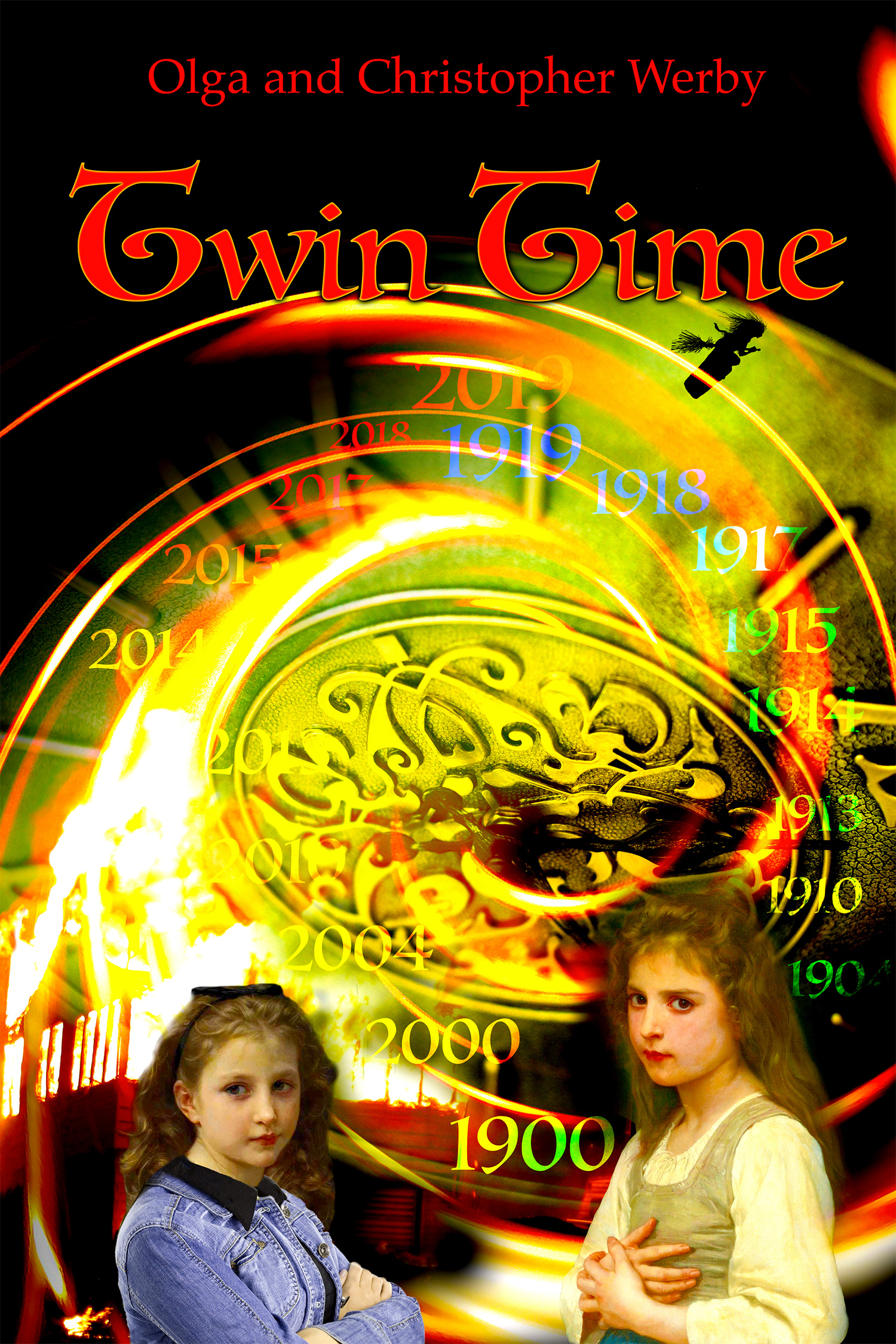

There are doors without and doors within. Some doors lead to a career, others to the special people in our lives, and still others to the mysteries of our inner selves. There are doors to stride through with purpose, and doors to peek through with trepidation. But maybe once in a lifetime there is a door to another reality, a door that connects worlds within multiverses. Be warned: stepping through such a door changes your life forever. So be careful what you wish for.

One: 2019 — Fire

“Alex?”

“Dad?” There was noise on the line. Alex heard the sirens of emergency vehicles. She had a sick feeling, making her hand tremble as she jammed the cell phone harder against her ear. “Dad!”

“Alex, honey, there was an accident.” Alex’s father sounded all wrong. “I need you to get to Mills Hospital on the Peninsula right away. Okay?”

“Dad? What’s going on? Is Sasha all right? You’re really scaring me.”

“There was a fire. Aunt Nana has been taken to Mills. Can you get someone to drive you? Mom and I will meet you there.” There was more shuffling, and Alex heard someone tell her father to move. Alex’s father shouted something back, but it was muffled and she couldn’t understand what was being said. Then the line went dead.

Alex held the phone in front of her, hoping to get more information from the mute device. Her legs felt weak as she tried to stand. She needed to borrow a car. It was midday, mid-week, and everyone was in class. Alex had been about to go as well. She was minoring in Russian Literature, and her teacher didn’t make late arrivals welcome.

Her roommate’s keys were on top of her desk. And then they were in Alex’s hands–her subconscious mind had made the decision before she had. She would text an explanation later.

At this time of the day, UC Berkeley was at least an hour away from San Mateo–the small town on the San Francisco Peninsula where Mills Hospital was located. It would be at least an hour before Alex knew what was really going on.

She ran out the door.

“Ma’am? Ma’am?”

The police officer had been trying to speak to the woman, Emma Orlov, but she was clearly in shock, unable to respond. Another officer had been managing the woman’s husband, Greg, trying to convince him to escort his wife away from the scene of the fire.

A neighbor called the rest of the family while the police started the evacuations of nearby homes. The house had already burned to the ground, but the fire stubbornly refused to go out, and the firemen worried it might jump to the neighboring structures.

There had been only one critical injury: an old lady they had pulled from the fire. An ambulance had already taken her to the hospital. However, Mr. Orlov insisted that their daughter was also in the house. The girl was autistic, he said, and mute except for her own name: “Sasha.” The firemen hadn’t been able to locate the girl, but at least there was no evidence that the girl had died in the fire–although it was too early to tell for sure. Still, an alert had been issued: “Svetlana Orlov, a nineteen-year-old special-needs woman, missing after house fire.”

“Sir? We’re going to have to ask you and your wife to leave now. It’s getting dark.”

“She’s in there somewhere,” the girl’s father said in a flat tone. “I know it. I dropped her off myself.”

The officer realized he wasn’t going to be able to get the parents to leave voluntarily. He looked around. The trauma center people should have been here already.

He looked back at the house. It was one of those old mansions built in a Spanish style almost a century ago–stucco and tile with a clay roof–one of the first constructions in the hills of San Mateo. It had been quite lovely, but now it looked like a bomb had exploded inside. Hardly anything was left standing. If there was a body in there, it might take a while to find it.

He shook his head. He had been one of the first on the scene and had been there when they pulled the elderly woman out. She said she was alone; she was adamant about it. She was badly burned, but before they took her away, she insisted that they get in touch with her lawyer. Strange, he thought at the time, but people tend to do strange things when their world goes up in flames.

Still…

Alex hated hospitals. The smell of death was always just barely noticeable underneath all the sparkling surfaces. Now she stood beside her great-aunt’s hospital bed. The woman was being kept alive by some futuristic spaceship-like life support system.

“Alexandra Orlov?”

Alex turned to see a small man in an impeccably tailored conservative suit standing by the door of the intensive care unit.

“I’m Alex,” she said. Who is he?

“Alex. I’ve heard so much about you.” The man smiled like he was a family friend. Alex found the strange intimacy of his expression both unnerving and patronizing. Where are my parents? The hospital’s reception staff had informed her of the fire, but her parents had not responded to her texts or answered their cell phones.

“I haven’t heard of you. If you’ll excuse me, my Aunt Nana is in there.” Alex tried to maneuver around the man to get into the room.

“I know. Nadezhda Orlova asked me specifically to talk to you.”

“While in intensive care?” Alex was getting annoyed. She knew some people were drawn to tragedy, and this man was keeping her from going to see Aunt Nana. She looked around for a nurse or a doctor or an orderly–someone who could get rid of him. Only family was allowed on this floor, and Alex was sure he was not family.

“I can assure you that Ms. Orlova was very specific. If anything were to happen to her, I was to find you right away. You see, I represent your great-aunt’s estate–”

“Don’t you think this is a very inappropriate time?” Alex was horrified. She was only nineteen and dealing with a family emergency on her own. Where are Mom and Dad? She certainly wasn’t qualified to be dealing with legal implications right at this moment, if ever.

“I am here on Ms. Orlova’s instructions.”

Deciding to go ahead and be rude, Alex tried to push the man aside. But he wouldn’t budge–he was stronger than he looked.

“Alex.” He reached out to her, but she pulled away and stepped back. “It’s very important that I speak with you right away. Please.”

Alex was confused and frightened. There was no one around to help, and Aunt Nana was unconscious, swaddled in all that technology, beeping and whooshing, the music of death. “What do you want?” she asked.

“I want to talk to you about Sasha and your Orlov family in Russia,” the man said.

There had been no Orlovs in Russia for over half a century, as far as she knew. Except…

Alex almost sat on the floor–it was just too much. But the man took her by her elbow and guided her to an empty nursing station just down the hall. He deposited Alex into one of the two rolling chairs and sat in the other one.

“What do you want from me?” Alex asked at last. “And what do you know about Sasha?” Please tell me Sasha’s okay. Sasha was Alex’s identical twin. But while Alex was a vibrant young woman studying at the University of California in Berkeley, her sister was profoundly autistic. Aunt Nana was one of the few people Sasha responded to, and today would have been one of the days she spent with her, giving their mother a much-needed break.

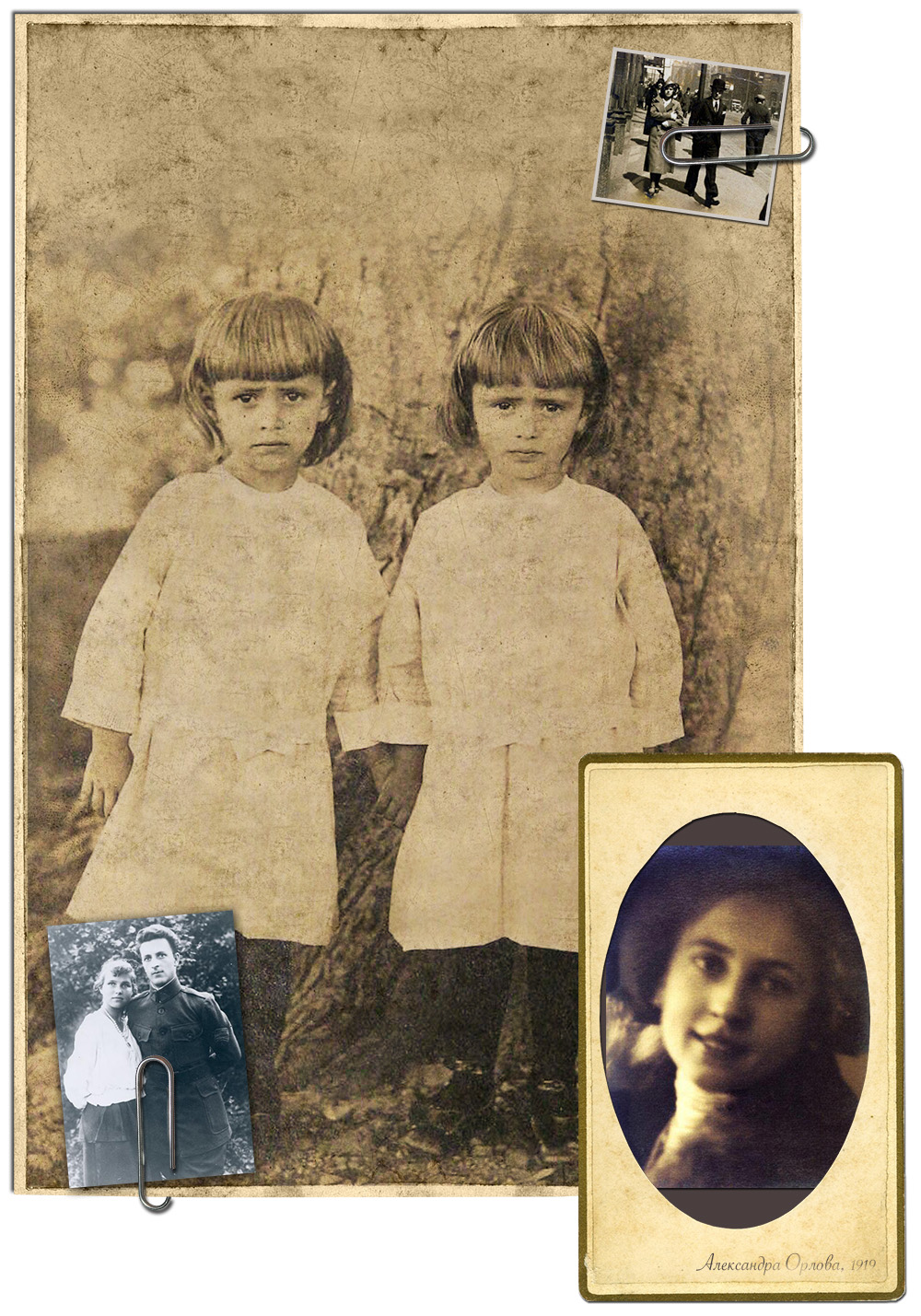

The man opened a briefcase–one of those superfine leather ones that Alex always imagined were carried by old lawyers. He carefully took out an envelope and gently slid out a few old sepia photographs. Alex couldn’t help but lean over and look. And what she saw took her breath away.

The photos were faded yellow and obviously very old. And yet the faces staring back at her, through the veil of time, were familiar. Very familiar.

The biggest photograph, which also looked the oldest, showed young twin girls dressed in identical white old-fashioned dresses and wearing black shoes and stockings. They were the faces of her and her sister.

Alex wanted to say that these people were fluke lookalikes–girls from another generation who just happened to bear a striking similarity to her and her twin sister–but she knew what she saw. The one girl was clearly her, Alex, and the girl she was holding hands with was just as undoubtedly Sasha. They appeared to be about three or four years old.

Alex flipped through the pictures. Two smaller photos showed a woman and a man. The woman looked like Alex, but a bit older. The man she couldn’t quite identify, but he did look familiar.

And then Alex found a photo of herself that looked like it could have been taken today–except for the fur hat and collar and the high-necked white shirt. The Alex in this picture was her, at her current age. It was like looking into some faded mirror, some alternate reality.

Alex flipped the photo over. On the back, in Russian, was printed a name and date: “Alexandra Orlova, 1919.”

Boris Blackburg was observing Alex carefully, judging her emotional state and her ability to comprehend what he was telling her. She seemed very confused. He wasn’t surprised. This was the strangest assignment he had ever accepted. At first, he thought it was some silly notion of a well-to-do old woman. But as the years passed, he got to know Nadezhda well, and he liked the old woman, eccentricities and all. And as he got to know the Orlov family as well–vicariously, of course—the assignment grew more and more strange and intriguing.

Boris was also well compensated for his work. He was going to ensure Nadezhda’s wishes were followed. Alex Orlov would inherit her great-aunt’s estate and all the accompanying strangeness that came with it. He would make certain of it.

“Where did you get these?” Alex asked.

“Nadezhda, your Aunt Nana, gave these to me about eighteen years ago, shortly after you and Sasha were born.”

“I… I…” Alex seemed to want to say something, but couldn’t get it out. Boris was prepared to give her time, as long as her parents didn’t interfere with his mission by arriving too soon. At least the girl was now of age and the complications of guardianship had gone away–but he needed to complete his assignment before her parents arrived and complicated matters.

“Who’s the woman in this photo?” Alex pointed to a small black and white print of a man and a woman walking on the street. The image was very small, and it was difficult to identify the people, both of whom were wearing hats.

“Who do you think it is?” Boris asked. He knew, of course–Nadezhda had identified most of the photos for him, and there was information written on the back of most.

“I don’t know. But… it looks like… me?” Alex’s voice was small, barely audible.

Boris nodded.

Two: 2004 — Great-Aunt Nadezhda

Emma tried to relax in the passenger seat of the family car. Svetlana and Alexandra were strapped into their car seats in back, Svetlana whimpering softly and Alex sleeping. They were all on their way to see Nadezhda Orlova.

Emma Orlov had never been clear just how her husband was related to the woman; when she pressed, he told her that she was his grandmother’s brother’s daughter. But regardless of the precise relationship, everyone called her “Aunt Nana” and treated her like a great-aunt on account of her age.

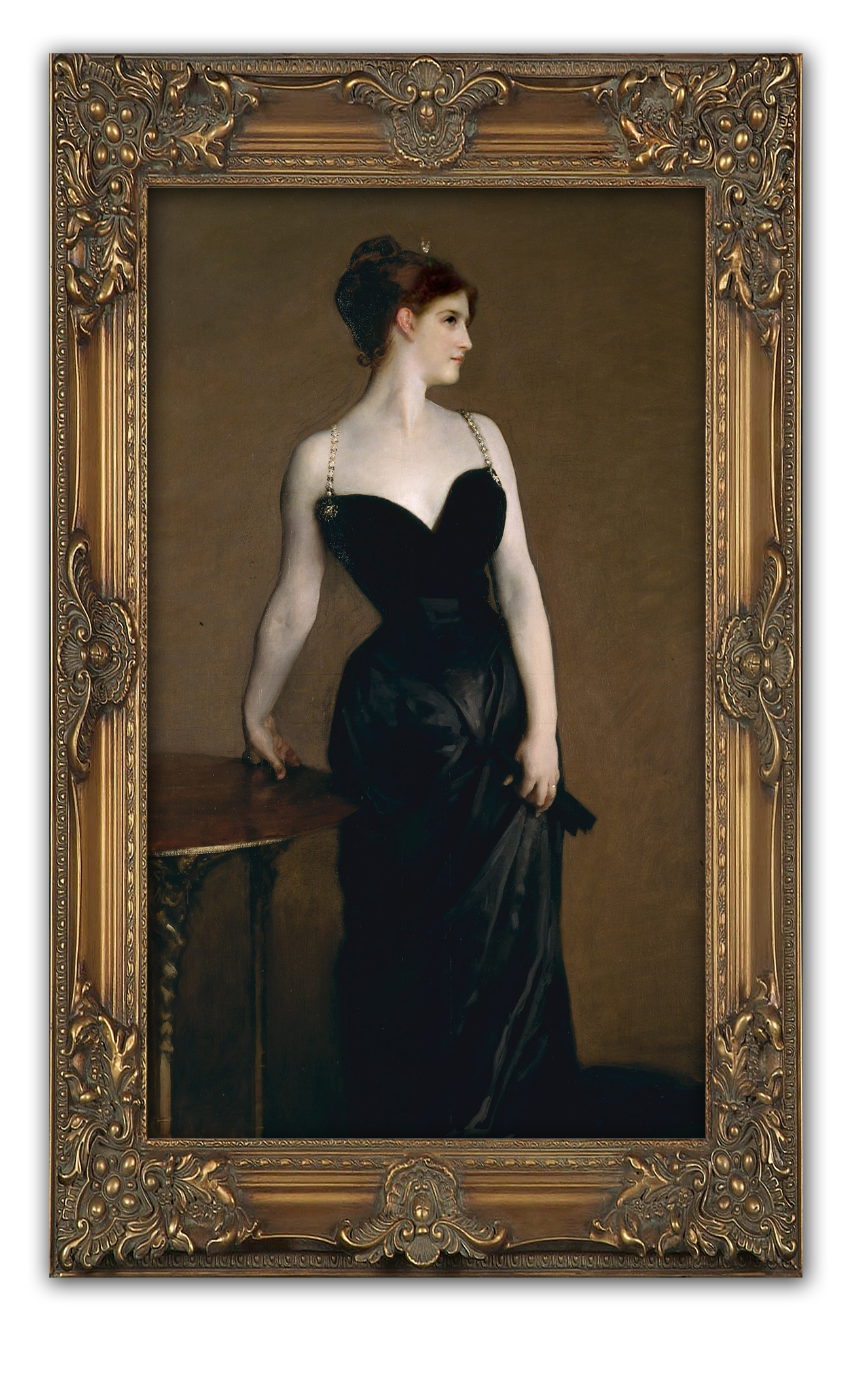

What was clear, though, was that Greg was very fond of her. He even insisted on naming one of their twins Alexandra in honor of Aunt Nana’s mother. Emma didn’t mind. It was a good, powerful name, and from the photographs she had seen of the portrait hung in the great room of the old family house in San Mateo’s hills, Emma thought Alexandra Orlova looked worthy of a namesake.

Emma had chosen the name for their other daughter. Emma had always liked the name “Svetlana,” meaning “light” in Russian. Power and Light–great names for identical twin girls of Russian heritage.

Greg had been born here, in America, as had his parents. But his grandparents had immigrated to the United States in the late 1930s, escaping from the newly established Soviet Union via Manchuria some time after the Bolshevik Revolution. Greg’s parents were only kids when they lived in the exiled Imperial Russian community in China, but they talked about it like they’d spent a lifetime in the old country. And it was Alexandra Orlova who had been one of the first to leave Manchuria for America, and who had orchestrated the escape of the rest of the family.

Emma had never met the great lady Alexandra Orlova–she died in 1975, when Greg was just five–but he said he remembered her. Emma didn’t really believe him; childhood memories are often formed from photos and stories, rather than from real memories of the events themselves. And Emma had only met Aunt Nana twice before.

The first time was at the wedding. Emma felt an immediate attraction to her, as if they’d known each other forever. But they lived on opposite sides of the continent, so Emma didn’t see Aunt Nana again until the girls were born. Aunt Nana hadn’t announced she was flying in for the birth, but she was suddenly there at Brooklyn Hospital’s maternity ward. And when Aunt Nana held Emma’s newborn daughters for the first time, Emma thought it felt right. Family is a very strong force.

Aunt Nana was thrilled when Greg told her of their decision to name one of the girls Alexandra; she even cried. And later, she set up an education fund for the girls–an amazing gift.

Everyone will tell you that having twins is very difficult–it’s more than twice the work—and Emma and Greg hardly slept the first couple of years. Now that the girls were three, it should have been getting easier. But life never turns out how one plans it. While Alexandra–Alex–was thriving and turning into a clever and beautiful little girl, Svetlana’s developmental trajectory was quite different.

The regression started when Svetlana was about eighteen months old. It was difficult to spot at first, and everyone told Emma she was just imagining things. But when the girls were together, it was obvious that something was very different about Svetlana. It took almost two years to get a final diagnosis: autism. By then, the sunny blond little girl couldn’t even speak. It was like watching the light drain from their Light Girl, their Svetlana.

Aunt Nana offered Greg help in getting the services Svetlana would need. California was better than New York, she said. The autism epidemic had hit California hard, and the state had responded by making services available. Moving across the country, away from family and friends, was a hard family decision, but Greg and Emma didn’t hesitate: Svetlana’s well-being came first.

Aunt Nana and her lawyer, a careful and elegant man named Boris Blackburg, helped with the arrangements: selling and buying a house; getting connected to doctors in the Bay Area; helping Greg get a new job at a tech startup, and with a significant raise, too. And Aunt Nana did it all without being too clingy.

Emma’s mother, a New Yorker herself, cried at the news that her daughter would be moving so far away, but she agreed with the decision. It was better for Svetlana, end of story. She came out to California to help set up their house and get Emma organized, and then she returned to New York with a teary farewell.

That was a week ago. And now they were headed to Aunt Nana’s house.

This, then, would be the third time that Emma would meet Greg’s great-aunt. The woman had been wonderful to them, but Emma still felt trepidation showing the girls to her. It was almost like, as a mother, Emma felt responsible for Svetlana’s failure to thrive. Like it was all her fault. She knew that such thinking was silly, but she couldn’t help it. It was how she felt.

And lately, she’d been taking that anxiety out on Greg. They’d been fighting for the last three days. Emma had even tried to cancel the outing to Aunt Nana’s house, but Greg insisted. Now they were driving in angry silence.

When they arrived at the house, Greg hopped out. He and Emma had the whole “get the girls in and out of the car” routine down pat–they were a good team, a well-oiled machine. Greg picked up sleeping Alex and carried her inside while Emma waited in the car with Svetlana. Emma had hoped the ride in the car would knock her out, but no such luck–the girl had been restless all the way here. Now she would be a disaster inside–new place, new person, no sleep.

Emma took a deep breath. So be it. Aunt Nana knew how it was, she just hadn’t witnessed it firsthand yet. Emma wiped a tear from her eye and waited for Greg to return.

Greg came back smiling. He loved the great old rambling house. He had told Emma endless stories of his adventures here. When he was little, in the ’70s and early ’80s, he had spent his summers here. He and his older brother Nick had been free to explore the three-acre estate, climbing the old knobby oaks, eating apples right from the trees, swimming in the pool, and playing in a big tree house Aunt Nana had built especially for them. He spoke of it as a magical place, a great house in which to spend a childhood and build happy memories.

Greg said that Aunt Nana had spent most of her own childhood at the house, too. Her mother built it for them in 1935, right after they immigrated to America, a few years before the rest of the family arrived.

Emma looked at the house now. It looked just as it had in the photos she’d seen: a two-story Spanish stucco house with a large terracotta tile roof. Little balconies were surrounded by wrought-iron railings painted dark orange, and wisteria climbed up the sides of the house, dripping clusters of lilac flowers. Old hand-painted tiles provided architectural accents, while stately old trees encircled the house and ran along the property line. It was very much a fairytale dream home. Alex will like it here, Emma thought.

“Come, let’s get Svetlana.” Greg leaned in to get their daughter. Emma braced herself for screeching, but it never came. Svetlana allowed her dad to get her out of the car seat and be carried inside. Emma followed, loaded down with endless bags full of diapers, changes of clothing, baby food, and toys.

It was early summer, and the day was warm and sunny, but inside, the house was cool and dark. Emma stopped to drop most of her load by the front door, and then she and Greg stepped into the great room.

Alex was already running circles around a low coffee table, laughing like a tinkling bell. Aunt Nana was seated on a sofa, clapping her hands each time Alex passed. But she looked up as soon as Greg walked in with Svetlana.

Emma felt herself tense up. Greg hesitated too. How would their Svetlana react to this strange house, this unfamiliar person?

Aunt Nana rose and walked over to them, stopping right in front of Greg. She leaned in to catch Svetlana’s eyes. The little girl looked at Aunt Nana and extended her arms–the universal child gesture for “hold me.” And just like that, Aunt Nana was holding Svetlana, stroking her back, murmuring something softly in her ear.

Emma forgot to breathe. Greg just stood there, his arms hanging by his sides. Svetlana never let strangers hold her, and she never asked to be picked up. Her first reaction to anything new was a high-pitched screeching. Yet here she was, happily being carried by a stranger.

“So, what’s your name?” Aunt Nana asked Svetlana.

“Aunt Nana, she—” Greg began, but Aunt Nana cut him off with a stern gaze.

“What’s your name, little one?” she asked again.

“Sasha,” the girl said.

It was the first word she had uttered in over a year.

“That’s a beautiful name,” Aunt Nana said approvingly. She sat back down on the sofa with Svetlana–Sasha–on her lap. A larger-than-life portrait of Alexandra Orlova hung on the wall behind her.

Emma just stood there and wept.

“What did you think of the girls?” Boris Blackburg asked when Nadezhda Orlova, Aunt Nana, called him after the family left her house.

“Alexandra?”

“Is she the one?” Boris knew well the large portrait of Countess Orlova in Aunt Nana’s living room. He was also very familiar with the Orlov family photos and documents from old Russia. There were quite a few images of the twins, showing them growing up in a rural settlement founded by the Orlov family patriarch almost two centuries ago, northeast of Saint Petersburg.

“She seems bright and sunny. Just like we have always imagined,” Aunt Nana said. “But Svetlana is worrisome. I had no idea how profound her disability was. She did tell me her name was Sasha though. So that was something.”

“Sasha? As in short for Alexandra?”

“Yes. I know, it’s strange.”

“So we… you have two potential Alexandras?” Boris asked.

“That has been true from the beginning.”

“Yes, but–”

“Nothing’s changed,” Aunt Nana cut him off.

“Of course.” Boris let it go; his job was to serve the Orlovs. But this was certainly an unexpected development.

Three: 2004 — End of First Summer in California

It had been five months since they’d moved to California. The girls had adjusted really well, and Greg liked his new job. But Emma had planned her life very differently from the way it was unfolding. At one time, Emma wanted to be a journalist; Sasha’s diagnosis had put an end to that dream.

It wasn’t that Emma felt unvalued. It was just that, sometimes, when she was lying in bed in the dark, she felt a little lost… trapped, even, if she allowed herself to feel sorry for what she had lost. She wouldn’t give up her little girls for anything, of course, but she fervently wished that Sasha wasn’t autistic. It felt completely unfair. Not just to Sasha, but to her.

Sometimes, in the depth of the night, Emma cried. But then the morning would come, and she’d get up, smile, and get the girls dressed and fed. She would deal with the therapists that showed up at their door every day after breakfast. She would take the girls out for a walk around the park or to Aunt Nana’s. She shopped, she cleaned, she played with the girls, she read to Alex. Greg did most of the cooking, and each night after dinner he’d help with bathing and putting the girls to bed.

And then she’d fall asleep early, at least until sometime in the middle of the night, when she’d awake and cry silently, trying hard not to disturb Greg.

Today, Emma had a dentist appointment, so she was dropping the girls off at Aunt Nana’s house for a couple hours. She hated to impose like this—taking care of four-year-old twins was difficult for anyone, and Sasha (as they’d called Svetlana ever since that first meeting with Aunt Nana) was particularly difficult. Except that Sasha seemed to magically change whenever she entered the great house. Emma wasn’t sure if it was the place itself or Aunt Nana, but her little girl relaxed when she was there; Emma could feel the tension melt inside those little tight muscles of hers. It was like she could… breathe easier. It was also the only place where Sasha would speak, although she only ever said that one word: Sasha.

And because of the wonderful effect Aunt Nana had on Sasha, Emma had been trying to find ways to drop by the great house. She would pick up an extra cake at the store and bring it over with the girls, or she’d “find herself in the neighborhood” and make a quick stop to say hello, or she’d go shopping at the farmers’ market and get a great deal on some fresh local produce that she just had to share. Greg was worried that they were taking up too much of Aunt Nana’s time and energy–she wasn’t a young woman, after all–but he, too, noticed the remarkable transformation in Sasha when she was with Aunt Nana, so he also helped find opportunities for them to visit.

Aunt Nana didn’t seem to mind. In fact, she made a point of actively encouraging them to come as often as they could. She installed a cover over the pool, since the girls were too young to swim there by themselves, and she put up a little fence around a flat bit of grassy lawn at the back of the house—the “play garden,” as Emma had started to call it–and had a sandbox built there. Alex loved to run around there, playing with plants and flowers and building things out of sand.

The great house was on a hill, with the back a full story below the first floor in the front. Part of the basement area was used to store garden and pool supplies; the rest, with a separate outside entrance, was originally a small guest changing room and a bathroom for guests using the pool–but the changing room had now been transformed by Aunt Nana into a playroom, stocked with toys and equipped with small napping cots.

Surprisingly, Sasha loved the little “play garden” as much as her sister. It was right in front of the storage room, and Sasha liked to sit by the little wooden door and play with the snails she found there. The whole wooden door was covered with little slimy trails that Sasha would trace with her fingers. She could do that for hours.

But it wasn’t just the girls who were happy at the house. It was Emma, too. When she brought the girls over, it was as if, if only for a brief period, she could let go. Life didn’t seem so overwhelming. It almost felt like everything was “normal”–the way she imagined other families felt all the time.

Now she sat and watched as the girls settled into the play garden. She had arrived here well ahead of her appointment to allow the twins time to get situated before she left them alone with Nana.

Alex stripped her clothes off and ran around naked in the grass, giggling. Sasha tried to do the same, but she had trouble–her hands were just not as dexterous as Alex’s. Emma jumped up to help–it was a sunny warm day, and she imagined the grass would feel good on bare skin–but Aunt Nana motioned for her to wait a bit. Emma had to forcibly stop herself. It was hard not to render immediate help, especially to Sasha, but Aunt Nana was right: she needed to let the girls do more things on their own.

Just a few heartbeats later, Alex ran to Sasha and helped her remove all her clothes too. Now the whole play garden was strewn with little socks, shoes, underwear, and cotton dresses. Sasha settled down to playing with her snails again, oblivious to Alex, Emma, and Aunt Nana. Emma knew she would be playing like that long after Alex had tuckered out and fallen asleep in the little bed in the playroom.

“I guess I should go,” Emma said as she picked up the clothing from the play area. She rubbed her temples; she was starting to get one of those headaches again.

“Have a good time, dear,” Aunt Nana said.

“It’s a visit to the dentist,” Emma said defensively.

“Oh, I didn’t mean it like that,” Aunt Nana said. “I just don’t want you to worry about the girls. They’ll be fine, I promise.”

“I’m sorry. Of course they will be,” Emma replied. “I just feel guilty–”

“Don’t. It’s all good. The girls are happy here. Isn’t that what’s really important?”

“Nana?” Alex walked over to Aunt Nana. She was smudged with dirt, and there were grass strands in her blond hair and sand on her lips.

“You didn’t eat sand again, did you, dear?” Aunt Nana asked, then repeated herself in Russian. On days like today, when Emma wasn’t around, she said everything twice: once in English and once in Russian. Alex was already picking up a few words of Russian. It was hard to tell with Sasha, but Aunt Nana had hopes for her as well.

“I made a cake, but Sasha won’t eat it,” Alex said. She had been the first, after Aunt Nana, to start calling her sister Sasha. Now they all did it.

“Let me see.” Aunt Nana walked over to where Alex had been making a cake in the sand. It was an extensive creation. The layers of her “cake” alternated sand with leaves and grass, and on top was a flower arrangement–mostly nasturtiums. From the look of it, Alex had nibbled on a few of the flowers.

Aunt Nana smiled. She had only introduced the flowers as a salad addition last week when the whole family came over for dinner, and here was Alex cooking with them already.

The nasturtiums were a particular favorite of the snails that Sasha loved to play with. Aunt Nana had forbidden her gardener from disturbing the snails. He must have thought she was demented when he discovered that she had been leaving little piles of nasturtium flowers and lettuce leaves out on the little stone wall next to the basement door for the snails to eat. But Sasha loved playing with the snails there, and Aunt Nana wanted to make sure there would always be plenty for her to play with. What was more important? Sasha, or plants? It was no contest.

Aunt Nana looked over to where Sasha had been playing–but the girl wasn’t there. Aunt Nana began to panic. It was like vertigo: standing on the edge of a deep drop, off balance, and all screwed up with fear and anxiety.

She rushed over to the little stone wall by the door. Snail shells were arranged in neat little rows, and a few live snails were slithering around them. Many slime trails led to the door. She pushed on it, and it swung open. She was sure it had been locked. The gardener must have forgotten to secure it this morning before he left, she thought.

“Sasha?” Aunt Nana called into the gloom.

The door led into the garden storage area, which wasn’t a good place for a naked, barefooted four-year-old girl. There were sharp tools inside, and the room was dark and dusty.

“Sasha!” she called again, real panic edging into her voice.

Alex came up to her and tugged on her skirt. “Nana?”

“Stay here, honey. I’ll just get Sasha, okay?” Aunt Nana’s voice came out false and syrupy-sweet.

“Nana?” Alex said again. The girl could tell something was wrong.

“Just a minute, okay? You wait right here,” Aunt Nana said. “I’ll be right back.”

She walked into the darkness of the basement. It had been a long time since she’d been this far in. This area always gave her a headache, and now was no different. “Sasha?” she called, but her voice came out small and hesitant. She didn’t want to disturb the gray gloom. Not yet, not now.

Walking carefully, pushing aside the endless junk that she purposely stored here, Aunt Nana made herself move forward. Soon she smelled the aroma of pine and heard the sound of chickens clucking. She didn’t want to walk any farther; she couldn’t. But she didn’t have a choice–Sasha was there somewhere.

Aunt Nana closed her eyes and tried to move forward. She kept her arms in front of her to feel the way. It wasn’t very far. Just a few more steps. She heard giggling up ahead–unmistakably Alex. Aunt Nana looked behind her. “Alex? Are you waiting for me like I asked you?” But she already knew the answer–Alex had somehow run ahead of her. Both of the girls were up there now.

Aunt Nana’s head was spinning. She had to sit down. She was in deep–deeper than she had ever allowed herself to go before. She put her head in her hands and thought. Did any of the photos her mother gave her come from this time? She wasn’t sure. Perhaps that one of the girls in matching white dresses? But they looked so serious in that photo; she had always assumed that they were older in that one.

This was not how Aunt Nana imagined this would happen. She had waited all her life for this moment, getting ready, planning. And yet now that it was happening, she had no control. She sat on the cold floor with her arms wrapped around herself, trying to hug away the terrible dread that was spreading inside her.

When Alex was born, Aunt Nana was sure she was the one. And later on, when the girl proved to be so bright and articulate, it was easy to see she would blossom into a powerful woman. Aunt Nana didn’t know that Alex’s twin would have problems, but when it happened, she didn’t think it would change anything. But now, sitting here waiting for the girls to come back, she saw nothing but complications. How will Sasha’s autism be received there? Does Alex have enough Russian to communicate? And how does this all work?

She remembered all the stories her mother told her–but those stories had always felt theoretical somehow. This was real. The girls were no longer here.

When will they get back? Will they even know how to get back? What happens if Emma returns before they do? What if something happens to Sasha? She doesn’t do well with strangers. Will they harm her unknowingly somehow?

Aunt Nana sat and rocked. There was nothing she could do. The girls were alone, naked, and completely unprepared.

She had failed them.

Four: 1904 — The Orlov Family

Sasha followed the juicy snail trail inside the room full of big machines and giant shovels and rakes–like the things that Alex played with but much bigger. Sasha was very careful. She didn’t want to knock anything down; people hated when she knocked things down. And she didn’t want to harm any snails. This was their home. There were even more snail trails here than outside.

Beside the door was a pail with lettuce leaves. Aunt Nana said the snails really loved to eat lettuce. Sasha didn’t like eating green food, but she was happy to feed it to her snails. During dinner one time, she put a snail on the table, and Mom yelled at her. Sasha was more careful now.

She picked up a small leaf–snails were small animals and didn’t eat that much–and went to find the snail bedroom. Every house had a bedroom. If snails lived here, that would be the place where they all slept.

As Sasha moved farther inside, things changed. For one thing, it smelled different. It smelled like floor cleaner. Sasha liked the smell of floor cleaner, but Mother had told her not to touch the bottle. Sasha was only trying to smell it, she wasn’t going to drink it–it was green. But Mother was really upset. Sasha didn’t know why, so she decided she would only smell the floor cleaner when no one else was around.

Smell wasn’t the only thing that changed. As Sasha moved deeper inside, she found that she could walk on her toes. Alex could walk on her toes any time she wanted, but Sasha never could. Until now. Sasha weaved in and around the various obstacles in the dark, tiptoeing just like Alex. She loved being so perfect–she didn’t touch a single thing, didn’t knock anything over, didn’t even make a sound. She was very proud of herself. She loved how the snail home made her feel.

There was a strange noise, something Sasha had never heard before. It sounded a bit like a sound-making toy, but Sasha was sure it was a living thing. And as she walked toward the noise to investigate, the floor changed. It was no longer hard stone, but dirt, like outside but without any grass. She knew she was still inside the house, but it felt different.

Then Sasha saw sunlight streaming underneath a door made of wood boards. She could even see sun glinting between the boards. She pushed the door, and it opened.

Outside was a little garden with grass and flowers. It wasn’t like Aunt Nana’s garden, but it was very pretty. There were birds running around–big birds. Chickens, Sasha thought. She had seen pictures of them in a book. And they were eating her snails! Sasha ran out into the sun to stop them.

Alex was very good at being able to tell when grownups were unhappy. People tended to be unhappy around Sasha. Alex didn’t know exactly why that was, but she thought perhaps it was because Sasha did things her way and didn’t talk. And right now, Nana wasn’t happy–because of Sasha.

Alex and Sasha had divided the garden so that Alex got the flowers and sand and Sasha got the snails. That was fine with Alex–she didn’t like how the slime felt on her fingers. But Alex did bring special snail dinners for Sasha, made of leaves and petals from the orange flowers. She had planned on bringing some lettuce from the kitchen the next time they came over to play, but she had forgotten.

Just a little while ago, Sasha had been playing with the snails, as always; but now she was gone, and Nana was upset. Nana thought Sasha had gone into the dirty room where the gardener kept his tools. Dad said they were sharp and dangerous, and that Alex and Sasha weren’t supposed to go in there. But Alex guessed that Sasha went in to find her snails.

Alex wanted to make her Nana feel better. She pulled on her skirt, but Aunt Nana told her stay behind and wait. And Alex would have waited… but Aunt Nana sounded so unhappy.

Alex decided to go get Sasha and bring her back to Nana.

She walked inside the gardener’s room and carefully made her way through all the big tools. She didn’t call out, because she didn’t want Nana to get upset with her. It was dark, but before long there was a door, and it opened onto a sunny garden with chickens. Alex ran through the door and saw Sasha chasing them.

“Sasha!” she called.

“They’re eating my snails!” Sasha cried back, very upset.

“Let me see.” Alex ran over to her sister, who was holding a collection of five fat snails that she had apparently rescued.

“These are very nice,” Alex said. “I saw a bucket of lettuce leaves. You can feed them,” she offered. It was nice to actually speak with Sasha. Back home, Alex did all the talking for both of them.

“I think chickens love to eat snails,” Sasha said. She didn’t seem to be surprised by her ability to speak here. Perhaps that’s just how it was–Sasha spoke here and didn’t in California.

“Do you want to save them or feed them to the chickens?” Alex asked. She was good either way, as long as she didn’t have to touch the snails.

Sasha considered. “Do you want to feed a chicken?”

“Okay.” Alex found a leaf on the ground, and she spread it on her palm. “Can you put one on here?”

Sasha placed one of her snails on Alex’s outstretched hand, right on top of the leaf. Sasha knew that Alex didn’t like to touch snails. “Here,” she said.

Alex bent down and called, “Here, chicken, chicken, chicken.”

“I don’t think they speak English,” Sasha said. “Try calling them in Russian.”

“I don’t know the word for chicken,” Alex said. She tried to remember if Nana had ever told them, but if she did, Alex couldn’t remember it.

“Cooritza,” Sasha said.

“Here, cooritza, cooritza,” Alex called.

One of the birds finally noticed her and came over. It was a big bird, and it looked even bigger when it was closer. Alex panicked and threw the snail at it. The bird ran away.

“Sorry, Sasha. It looked scary.”

“It’s okay. She’ll find it later,” Sasha said. She dropped her stash of snails on the ground and started walking off.

“Where are you going?” Alex asked.

“I want to see if there are other animals here,” Sasha replied.

Alex looked back at the door they had come through. It was the door of a small shack leaning against the rocky side of a hill, and this chicken house didn’t look anything like Nana’s home. That made Alex very uncomfortable–it’s going to be hard to get back to Nana’s, she thought–but Sasha seemed fine.

Together they walked across the chicken enclosure to a small wooden gate. But before they reached it, a large colorful bird swooped down and attacked them. The girls screamed and ran.

“Get out of here!” a man yelled, and he kicked the rooster away from the girls. “Are you good, little ones?” he asked.

At least, that’s what Alex thought he said. The man was speaking in Russian, and she didn’t entirely understand what he was saying. But he saved them from the bad bird and he was speaking in a gentle voice.

The man was wearing a loose shirt that had stopped being white a long time ago. But it was clean, and so were his brown pants, which were not only loose but too short, hanging about a foot off the ground. He was barefoot, with little bits of grass sticking out between his toes. The soles of his feet were completely black from dirt and slightly cracked; it looked like he was used to going without shoes. His eyes were brown, and his head and beard had a few streaks of white in otherwise red hair. He had a very kind face, full of happy wrinkles and smile lines. He looked like he laughed a lot.

Sasha immediately liked him. She ran to him and hugged him. Alex hung back; she wasn’t sure what was the right thing to do.

“There, there,” the man murmured as he bent down to check if they were hurt. Aside from a few scratches and dirt, Alex and Sasha were fine. “Do you have a name? Where’s your mama?”

“I’m Sasha, and this is Alex,” Sasha answered in Russian. This was one of the phrases Nana had repeated for them again and again.

“Where’s your mama, Sasha?” the man asked.

The girls knew the word “mama.” Perhaps this man would take them back? “Mama,” Sasha repeated, and pointed back to the small shack surrounded by chickens.

The man’s face changed. His expression made Alex uncomfortable, and she stepped away, but Sasha still clung to him. “Papa Kolya,” the man said, pointing to his chest. “Kolya,” he said again.

“Kolya,” Sasha repeated.

The man nodded. “Let’s get you girls cleaned up and fed,” he said, smiling. He picked up Sasha in one hand and offered his other hand to Alex. She hesitated, but then allowed the man to pick her up as well; the pine needles were hurting her feet.

Papa Kolya carried the girls to a big wooden house. Every window, every doorframe, even the roof was decoratively carved–with flowers and animals or just interesting geometric shapes. The top corners of the house’s towers held little white firebirds, and the rest of the house was painted in many different colors. Alex thought it looked like a birthday cake, extra sweet.

In one of the windows, Alex spied a woman. She, too, was very colorful. The whole scene looked a lot like something from the picture books Nana read to Alex, and to Sasha too, when Sasha was interested in being read to. Alex liked the house very much. It also smelled of good, baked food, and Alex noticed that she was hungry.

“Mama Anna,” the man said, nodding toward the house. “She’ll know what to do with you two little dears.”

The woman who met them at the door of the pretty house was big–or at least she looked big to Alex–but kind. While the man talked with her in Russian, she set up a big metal tub in the kitchen. Other people were there, too, and then ran around getting things for her. Alex and Sasha were told to sit on a wooden bench, where they were given bread and milk.

The kitchen wasn’t at all like the kitchen in Alex’s home or at Nana’s. It was big. It had several wooden tables, plus benches and wooden chairs and lots of strange pots all around on the many shelves. One wall was almost entirely taken up by a huge wood fireplace–Alex had never seen anything like it–with logs piled up right next to it. And there was a bed up there on top of the fireplace, or at least Alex thought it was a bed because it was piled with all those pillows and a blanket. One would have to be very tall to get up to that bed, for it was higher than a tabletop.

Among the pillows of the bed, Alex saw a big orange cat spying on her. She really wanted to pet it. But the woman called Mama Anna made them put their glasses of milk down and get into the big tub she’d set up for them in the middle of the kitchen floor. The water was nice and warm, and Alex and Sasha splashed around a bit. Then a girl–the same one Alex had seen in the window–brought some soap and cleaned off all the dirt and grass that was stuck to their feet.

When they were done, Mama Anna dried them off. But she didn’t use towels-instead, she wrapped them in bedsheets. Sasha thought this was very funny and giggled. Alex liked that. Sasha didn’t laugh much at home.

“There you are,” Mama Anna said approvingly. “Clean as new.” Alex didn’t understand what she said, but it sounded nice. Then Mama Anna pointed to Alex and said, “Sasha?”

And Sasha giggled even harder.

“I’m Alex, and this is Sasha,” Alex said, pointing to her sister. Even though they were identical twins, people usually didn’t mix them up. But Alex liked that Mama Anna was confused. And Sasha kept on giggling.

The girl that helped wash them was sent away. There were many people crowding at the kitchen door and pointing to the girls. Alex didn’t understand what they were saying, but everyone was nice.

The girl returned with some clothes unlike anything Alex and Sasha usually wore, but Alex didn’t mind, and surprisingly, neither did Sasha. They were given matching white dresses, socks that went way up above the knees, and black shoes. The shoes were not very comfortable, and Sasha didn’t want to keep them on, but Mama Anna insisted. Then they were taken outside and made to stand next to a tree for a long time while Mama Anna and Papa Kolya talked. Some people from the house watched the girls, while a few others did something with a big black cage on sticks. It was all very interesting, and new, and exciting.

But Alex was getting tired, and wanted to go back to Nana. She looked around, trying to find where the chicken house was. She couldn’t see it from where they were.

“Sasha?” Alex pulled on her sister’s hand. “I want to go home now.”

“Okay,” Sasha said, and she just walked right over to Papa Kolya. “Cooritza?” she asked.

He looked down at her and nodded. “Cooritza,” he said, and he pointed behind the pretty house.

Papa Kolya and Mama Anna followed the two girls, who were walking hand in hand toward the chicken house. A curious crowd shuffled along behind them.

“Cooritza?” asked Mama Anna.

“I found the girls in the chicken enclosure. The old rooster attacked them,” Papa Kolya explained quietly.

“I’ll cook that old bird,” Mama Anna said under her breath.

“But as I’ve told you,” Papa Kolya said, “one of them, not sure which one now… well, one of them pointed to the chicken house.” He gave Mama Anna a sidelong glance to see if that generated a reaction. The woman didn’t even twitch an eyebrow at the mention of the small house built into the side of the cliff. Smooth as a pickle Anna was. Kolya took a deep breath and pressed on. “And you know what that means—”

“Yes, I do,” Anna cut him off. “It means less talk.”

“If you say so. But how are we going to get them back in there? Just push ’em?”

“We’ll see when we get there. Now stop talking. You’ll scare folks with such talk.”

Kolya gave her another look, then checked over his shoulder at the large procession trailing behind. It seemed that everyone had managed to find out about the girls somehow. There would be endless talk now. Endless. Kolya took an exaggerated breath, and Anna gave him a dirty look. He grinned sheepishly and made no further remarks.

The rooster was waiting for them on the low fence. “Shoo! I say, shoo!” Kolya yelled at the rooster. The bird didn’t move. But when Anna waved, that rooster jumped like his life depended on it. Which, to be fair, it did.

Sasha opened the door to the chicken house and slipped inside. With a quick wave to the nice people, Alex followed. It was dark and dank in there. But as they moved farther and farther inside, the smell of pine went away. The girls could no longer hear the chickens clucking or the people talking. Soon, they were in Nana’s arms.

And all was good.